For years and years generations of Arrowmen have swapped, exchanged and collected Order of the Arrow cloth and felt badges. Over 2,000 new pieces of OA insignia are issued every single year, many primarily for trading. However, while most Arrowmen and collectors of OA memorabilia only think of cloth badges, the earliest insignia of the Order were pins. The reason why it was pins in the beginning is because Wimachtendienk started as a fraternal organization, and pins were the insignia of choice for fraternities. The simple silver arrow pin served very much like a fraternity pledge pin. In the first Constitution of the Wimachtendienk written in 1916 Article III stated:

The tortoise shall be the general insignia of the Order; for the first degree the insignia shall be the arrow superimposed on the back of the tortoise; for the second degree the insignia shall be the triangle superimposed on the back of the tortoise. The pin of the order shall bear the above insignia; the pledge pin shall be the arrow. (Note – A First Degree / Ordeal member in 1916 was considered a pledge that had not yet sealed his membership in the Order and therefore there were only two “degrees” in 1916, the First Degree which would be equivalent to today’s Brotherhood Honor and the Second Degree which would be the equivalent of today’s Vigil Honor).

-Article III, Unami Lodge 1916 Constitution.

This explains why the earliest pins had no chains connecting the lodge totem and an arrow, and the original Vigil pin had no arrow or chain. Examples of all three of these original insignia pins of Wimachtendienk are known. The oldest known pledge arrow dates to 1919, and it is confirmed that arrow pins date back to 1916. The 1919 pledge pin is virtually identical to the silver arrow pin of today. The greatest difference is that the original arrow pins were poured into a die whereas today’s pins are die-struck (like a coin). The way to detect a “poured” pin is the slight meniscus on the back along the edge of the arrow. A second difference is that the spinlock assembly on the reverse has a square shaped pin.

The first reference to what would become a Brotherhood totem pin is found in the 1919/1920 ritual for what was now called the Second Degree Wimachtendienk where Sakima (Chief) states

Now, with the assistance of Pow-wow, I shall pin on your breasts the badge of the turtle, with the arrow pointing over your left shoulder, change your arrow bands to the left side, and giving you again the grip of the Order, declare you members of the Second Degree, and entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities of the Order.

In 1921 at the first meeting of the Grand Lodge similar rules governing insignia for local lodges were adopted. During the first year of the Grand Lodge the Order entered into an agreement with the National Jewelry Company of Philadelphia (NJC) and announced at the 1922 Grand Lodge Meeting that NJC had been selected as the “Official” jeweler of WWW. The Unami Lodge type I Vigil Honor Pin (then called Third Degree) is the only known Wimachtendienk pin bearing the NJC hallmark. Other pins known with the NJC hallmark are teen’s pins from Philadelphia Council camps: Treasure Island Scout Camp and Camp Biddle.

One rule created by the Grand Lodge Insignia Committee was that no two lodges could have the same totem. That was enacted so that members could identify where another member was from by simply seeing their totem pin. This is a throwback to the rules of heraldry, the concept that members could determine the status and local affiliation of another member by seeing their insignia, but non-members would not know what they were looking at. This is very different than today’s practice of usually stating in words what a badge represents. By the early 1930s the rule that no two lodges could have the same totem became impracticable because of the number of new lodges forming annually.

When pins were first used, they were mandatory. However, because of the cost of silver and gold, some lodges took years to first make them, and some did not make them at all. Later, the pins became optional. They also were always for civilian wear only. BSA Uniforms and merit badge sashes were never an appropriate place to wear a totem pin. This rule was not always followed, and many photographs of improper usage exist.

In 1923 at the urging of Minsi Lodge of Reading, Pennsylvania, a motion was made before the Grand Lodge to start using two-part pins; the totem of the lodge with a chain to an arrow guard pin. Minsi Lodge made the motion because they were using just such a pin, a gold wolf head with emerald chip eyes attached to an arrow guard pin. This new two-part pin had replaced Minsi’s original pin, which was a 1 ¾” tall bronze wolf head that was also not compliant with the Grand Lodge Constitution. The motion for two-part pins was defeated, but by 1927 this became the standard design of almost all totem pins.

NJC manufactured First Degree arrow pins and lodge totem pins. These were the only insignia authorized by the Order until 1926 when patches were first approved. The patches initially did not replace the pins as the official insignia. It was announced at the 1927 Grand Lodge Meeting that Hood and Company, Jennings Hood proprietor, had replaced NJC as the Official Jeweler of the Order.

In 1945 Hood and Company was bought out by J.E. Caldwell and Company, and they hired Jennings Hood to work for them and manage the OA accounts. Hood brought his high quality jewelers’ totem dies with him. This explains why Hood pins and Caldwell pins from the front look identical; only the back die with the hallmark was changed.

In 1948, J.E. Caldwell, as official jeweler of the Order of the Arrow, included a brochure in the packet of all attendees of that year’s National Conference, had several pages devoted to their catalog of totems in the first Order of the Arrow Handbook, and had a display at the 1948 NOAC. Members were encouraged to order these “Caldwell pins” through their lodges as well as individually.

Some lodges still had totem pins locally manufactured. Zit Kala Sha Lodge, Louisville, Kentucky, for example had their totem pin made by a local Louisville jeweler. Chicago, for its original lodges and the later chapters always locally made their totem pins.

By 1960 totem pins for Brotherhood and Vigil members had largely lost favor to patches. At a price often 25 times as much as that of a patch they were often cost prohibitive. By 1973 it was made official that Caldwell was no longer the OA’s jeweler, and lodges ceased ordering totem pins.

In general, lodges ordered their totem pins directly from the official jeweler. The pins would typically have the lodge’s totem attached by a chain to an arrow. Primarily these pins came in gold and silver and were for Brotherhood Honor and Vigil Honor (triangle added to totem) members only. Pins were an optional piece of insignia and could be ordered by Arrowmen through their lodge or council office. J.E. Caldwell had a number of “generic” totem designs. Individuals could order in any quantity these generic totem designs. To create a unique die for a totem a minimum order of 12 to 15 pins were required to avoid a hefty die charge.

Typically, the generic designs are more common because multiple lodges used them. When a pin design was made for only a single lodge, such as the pin used by Mattatuck Lodge of Waterbury, Connecticut, then the pin can be exceeding rare because as few as 12 total pins were made in the 1940s. Consider how rare a patch with 200 made might be from the 1950s, and it is easy to see why these pins are so scarce with such limited numbers made so long ago.

In the early years of Wimachtendienk virtually all pins were gold. There are exceptions; Minsi Lodge from Reading, Pennsylvania often did their own thing with insignia (likely the first to make a chenille badge and the first to make a two part pin and to use emerald chips for the eyes). They used a large expensive bronze pin circa 1921. It is believed that this totem pin was used to clasp the member’s arrow sash (before snaps became standard). By 1940 lodges started to more often use silver. By 1950 most pins were made of silver. Some lodges did order both gold and silver at the same time (such as with Semialachee Lodge of Tallahassee, Florida, that split their one order of 15 pins into six gold pins and nine silver pins) and some such as Blue Heron Lodge preferred gold pins.

There are multiple reasons that explain why totem pins are so rare. Because totem pins were made of precious metals they were relatively expensive. At a time circa 1958 when a silver totem pin cost $4.50, a patch only cost twenty cents. An Arrowman could buy more than 20 patches for the cost of a pin. As a result, totem pins were effectively issued one per lifetime. And since an Arrowman had to be at least a Brotherhood Honor member, who historically was treated more akin to the Vigil Honor of today, only a small fraction of a lodge was eligible to purchase a pin. Because the totem pin was optional many never bought them, and no one had reason to buy a duplicate. There are no known examples of Arrowmen trading their pins, so no collections of these pins historically existed. Recent collectors have assembled the only collections that have ever existed.

In the past 20 years an increased awareness of these pins has revealed that most lodges historically issued totem pins. Several hundred lodges are now known to have used them, a high percentage of these lodges before they issued their first cloth or felt badge. As each year passes more lodges are discovered to have issued a pin in their past.

Lodges also issued other jewelry. Chief’s charms and medals were a common way throughout the 1930s through the 1960s to honor a chief or adviser at the end of their term. Both Hood and Caldwell are known to have made these objects. Caldwell also made Vigil Honor rings, Vigil Honor necklaces and cuff links.

2

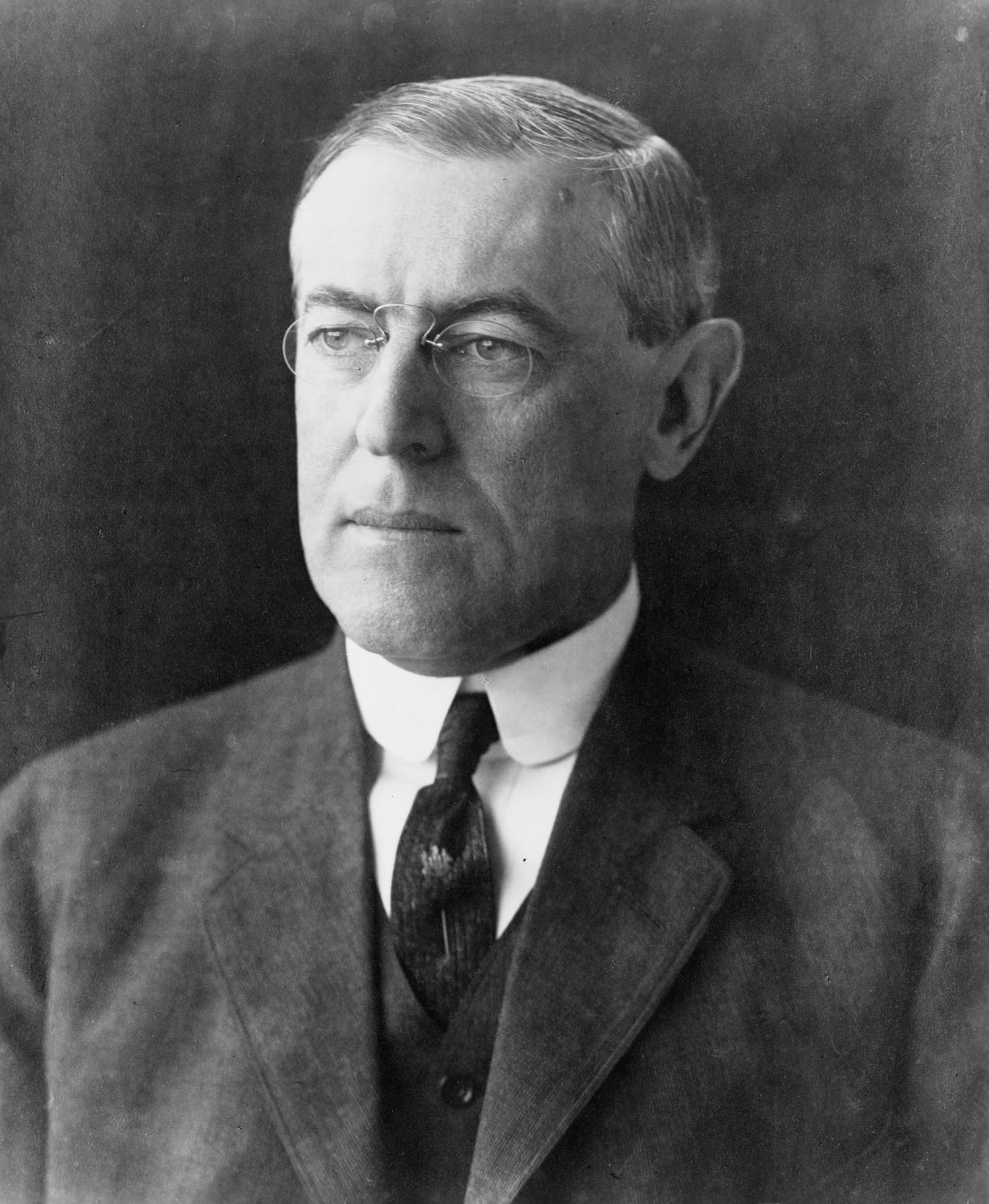

On March 4, 1913, Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated the 28th President of the United States. Boy Scouts provided crowd control for the inauguration and have served in that capacity at every inauguration since. While leading the nation during

On March 4, 1913, Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated the 28th President of the United States. Boy Scouts provided crowd control for the inauguration and have served in that capacity at every inauguration since. While leading the nation during